The Earth May Need to Get Rid of Us

Human beings have put themselves at risk for extinction by failing to recognize that Earth not only supports life, it is itself alive. We have put our needs and desires on a collision course with those of our planet and therefore may be cast off, according to the British scientist James Lovelock, author of the Gaia theory.

Worry about saving the Earth is misdirected and even arrogant, Lovelock has written. The planet can save itself, perhaps under conditions incompatible with human survival, such as a great rise in atmospheric heat. The question before us is: Can we save ourselves?

I first came across Lovelock in the 1970s, in the British magazine New Scientist, which published an article he co-authored with the American evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis, proposing his Gaia Hypothesis. He challenged prevailing scientific thought by arguing that the Earth purposely regulated its environment to make life possible, and that its climate could not properly be studied without taking into account the role played by living beings.

Lovelock developed the theory in the 1960s after he was consulted by NASA on how to design experiments for determining whether there was life on Mars. Before studying other planets, he suggested we study our own, as a whole.

When I read the article in the British science magazine, the first photograph of Earth from space was fresh in our minds, taken from the Apollo as it circled the Moon. That NASA image of a blue and white sphere glowing amid endless darkness, named Earthrise, revealed the fragility of our existence. Buckminster Fuller offered a metaphor, Spaceship Earth, which called attention to the need to prevent harm to our life-support system. Passengers on a spaceship must cooperate to survive. But a spacecraft is inanimate. It is built and piloted by humans. In contrast, Lovelock proposed —without calling it a living being--that Earth was “somehow alive,” and regulated itself, in purposeful ways, to sustain life. He named his theory The Gaia Hypothesis.

In evolution, Lovelock wrote, life forms adapted to a dynamic world built by the organisms themselves. The Earth’s atmosphere, which has kept the planet from heating up to a level that life cannot tolerate, was generated by living organisms. Almost all the oxygen in the atmosphere is the product of photosynthesis. Climate change projections are mostly based on modeling that does not take the input of the planet’s life into account, he pointed out. Predictions based on these models are therefore often incorrect. They fail to match what scientists observe in the real world.

I was thrilled by Lovelock’s insights. Intuitively, they made perfect sense. They also aligned with ancient beliefs in many cultures, which revered the Earth.

(The name Gaia—after the ancient Greek earth goddess—was suggested to Lovelock by William Golding, the novelist.)

Although many scientists dismissed Lovelock’s theory, over the years it has gained ground.

Several weeks ago, perusing one of the tiny free libraries that have sprung up in my neighborhood, I spotted “James Lovelock” on the spine of a paperback and pulled out The Vanishing Face of Gaia—A Final Warning, published in 2009, when the author was 90 years old.

“It’s arrogant to think that we can save the planet,” he wrote. “The Earth, in its but not our interests, may be forced to move to a hot epoch, where it can survive, although in a diminished and less habitable state. If, as is likely, this happens, we will have been the cause.”

Although we as a species have “the potential to be the progenitors of a much better animal,” our needs are now in conflict with those of the planet.

Just our breathing is a potent source of carbon dioxide, Lovelock wrote, “but did you know that the exhalations and other gaseous emissions by nearly 7 billion people on Earth, their pets and their livestock are responsible for 23 percent of all greenhouse emissions? If you add on the fossil fuels burned in the total activity of growing, gathering, selling, and serving food, that adds up to about half the total emissions. . . . It is not the carbon footprint alone that harms the Earth. The people’s footprint is larger and more deadly.” Even cutting emissions by 60 per cent would not be enough to prevent the overheating.

“I hope that a sufficient number of us are now aware that the lush and comfortable world that once we knew is departing forever. But I fear that we will dream on and, rather than waking, weave the sound of the alarm clock into our dreams.”

Less than a week after reading this I saw an obituary. James Lovelock died on July 26 this year, on his 103rd birthday. Meanwhile, we have continued to move toward our probable doom at an accelerated pace.

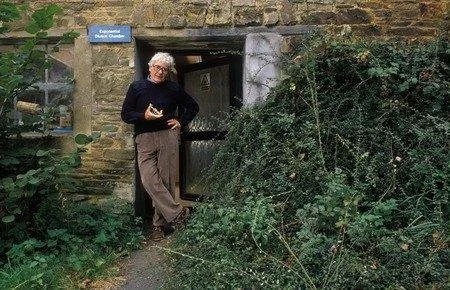

Professor James Lovelock in the 1980s or '90s. His lab is on the grounds of his home.

Homer Sykes/Alamy Stock Photo.